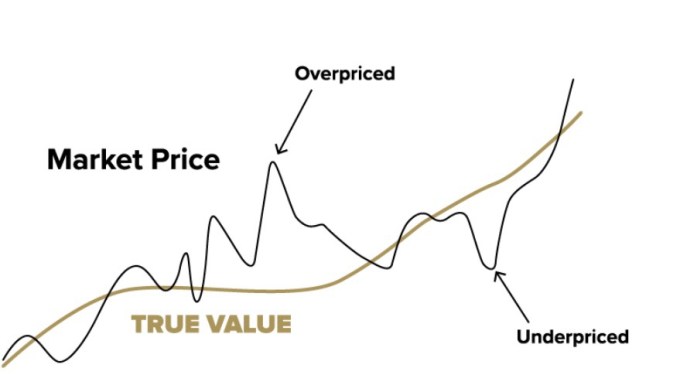

What is intrinsic value and why should anyone care? In my mind I’m able to separate the market value from intrinsic value. Understanding there is a divergence at times not only has helped me make some lucrative investments, but it also alleviates the anxiety when an asset drops in price considerably. It changes the game from a casino mentality to an investment mentality. I’m able to always look at the market price relative to what I think it’s worth intrinsically. If that price happens to get cheaper, I may like it even more, if I feel the underlying asset hasn’t changed in value much. Understanding value can also keep you from buying assets at ridiculously high prices, allowing you to recognize when prices have risen well in excess of intrinsic value. In contrast, If you own a non productive asset (meaning it produces no cash) and it falls in price, there is nothing that steps in and reinforces that the asset is a buy. It is pure speculation. Also, understanding that what I’m buying has value gives me confidence to not just dabble but to invest hefty sums every year. I’m not throwing a little play money in as they say and hoping for the best. I’m investing big sums. For example last year, I invested $71,975.08 into the stock market. The ONLY way I’d be comfortable doing that is knowing that what I’m buying has intrinsic value. Buying aggressively when I think the market price is far below what I think it’s worth intrinsically. With a productive asset, price is what you pay, value is what you get.

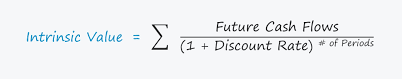

When determining intrinsic value you must decide what will come out of the asset and when. You must be able to answer 3 questions essentially: how much am I going to get, when am I going to get it and how sure am I? Another way to think about intrinsic value is the amount of cash an asset will deliver to you, minus the cash needed to maintain and grow over the course of its remaining life, discounted to present value. This is referred to as owner earnings or free cash flow. So if an asset will deliver to you 1 million of free cash flow in 10 years, what is that 1 million worth to you now in present day? Obviously you wouldn’t pay 1 million for it today, to wait 10 years to get the same 1 million back. So an investor will determine the intrinsic value, which by definition means the present value of future cash.

Being a great investor means seeing value where others don’t. A true investor isn’t paying a price and then hoping to god he can sell it later for a better price. This is speculation. Huge difference. An investor carefully analyzes an asset, calculating what it’s worth and then buys it for less. So that when the ink dries, you have already won. For example, they say in real estate that appreciation is icing on the cake, when you close you should have purchased for much less than it’s worth. So that on closing day you’ve already won. This is how the best investors consistently win. You find something that’s intrinsically worth a dollar and you buy it for 50 cents. You can do this analysis with any productive asset (productive meaning an asset that produces cash) Once you figure how how to calculate intrinsic value, it becomes a fun game. Markets don’t always price things correctly. Things are never 100% efficient. There are always opportunities to find things undervalued. You just have to know how to value assets.

Consider this example, as I feel it is a great example of a business that was bought for a steep discount to its intrinsic value. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway bought See’s Candy in 1972. See’s Candy is a specialty candy company with a dominant market position on the west coast. Still in business today. The price they paid was $25 million for the whole company. The business had a tangible net asset value of 7 Million (assets minus liabilities) and was earning 4.6 million pre-tax. However, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, the CEO and Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway determined that the company had such a dominant position that there was some untapped pricing power there. And to raise prices would take basically no capital. As a result, 20 years later the business was earning 42.5 million pre tax. Now of course, to determine the significance of the rise in earnings you must compare it to the amount of capital needed to fund those earnings. (1 million in added earnings that cost 1 million to produce added no value to the business) Over the course of that 20 years, ONLY 18 million was retained within the business, bringing that tangible net asset value to $25 million from $7 million. Throughout that time, $410 million of earnings that was not reinvested was handed over to Berkshire Hathaway, because it was not needed to either maintain or grow the business. So, essentially they laid out $25 million for a business that would return $410 million over the next 20 years in true owner earnings. That $410 million discounted back to the present value was the intrinsic value of See’s Candy in 1972.

Interestingly, the 20 year Treasury yield in 1972 was around 7.5%. (Investors use interest rates to discount money back to present value) Discounting the $410 million of capital that could be paid to owners and didn’t need to be reinvested, the present value of that future cash flow was worth between $80-$100 million dollars in 1972. They bought the whole company for $25 million. When you approach investing like you are buying a piece of an asset rather than trading a piece of meaningless paper around, your approach takes on a new meaning. And your batting average over a long time will be much better as a result. This concept is simple, calculating it is not so simple. Present value of future cash flow= intrinsic value.